12,000-year-old Aboriginal sticks may be evidence of the oldest known culturally transmitted ritual in the world

Aboriginal artifacts in Australia that were likely used for ritual spells may be evidence of the oldest culturally transmitted ritual on record.

The 12,000-year-old remains of two mini-fires and two curious sticks deep within a secluded cave in southern Australia may be evidence of the oldest known culturally transmitted ritual in the world, a new study finds.

The artifacts, which were analyzed in a new study that used both scientific analyses and Aboriginal oral history, may have been used in a ritual spell carried out to bring harm to another person.

The artifacts are similar to a ritual practiced by the Gunaikurnai, an Indigenous group residing on Australia's southern coast, which involved smearing a wooden object with human or animal fat and then dropping it into a ritual fire.

Given the parallels between the objects in the cave and the historically attested Gunaikurnai ritual, which was recorded by anthropologists in the late 19th century, Aboriginal elders sought out archaeological collaborators to excavate the cave, known as Cloggs Cave, and study the artifacts. Their results were published Monday (July 1) in the journal Nature Human Behaviour.

Cloggs Cave was partly excavated in the early 1970s. In an email to Live Science, study first author Bruno David, an archaeologist at Monash University in Australia, said "the cave was never used as a general camping place, but rather only for special ritual purposes. It first began to be used this way around 25,000 years ago, and continued to be used this way until at least 1,600 years ago."

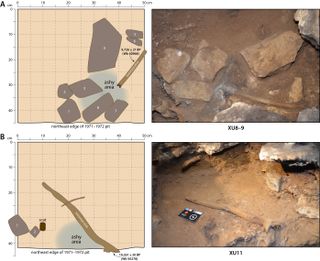

A subsequent excavation undertaken in 2020 by David and his team revealed two sacred ritual installations, each comprising a small fireplace with a slightly burnt wooden stick coming out of it. Radiocarbon dating of the sticks showed that one was between 11,930 and 12,440 years old, while the other was between 10,870 and 11,210 years old, making them the oldest wooden artifacts ever found in Australia.

Related: Mysterious rock art painted by Aboriginal people depicts Indonesian warships, study suggests

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The team found that both sticks had been deliberately altered, suggesting past people had trimmed, cut or scraped the sticks to make them very smooth. Further analysis showed that the sticks were both Casuarina, a native Australian pine tree, and that there were patches of an unknown residue on them. Chemical analysis of this residue using mass spectrometry — a technique that can identify individual molecules in a sample — revealed the presence of fatty acids, indicating that part of the stick had been smeared with animal or human fat of some sort.

Given the lack of food remains near the small fireplaces, the presence of a single smooth stick in each fireplace and the sticks' contact with fatty tissue, the researchers concluded that the 12,000-year-old installations they uncovered were used for a specific ritual purpose — one that appears to have been passed down over 500 generations from the end of the last ice age to very recent times.

"What these fire sticks tell us is that this is actually specifically about the culture of the Old Ancestors that continues to today," David said in a transcript of a conversation with Gunaikurnai Elder Russell Mullett. "Bringing in the community way — the cultural way — with some of the scientific techniques means that stories can be told."

The study sets a high bar for investigating ancient ritual practice, Ben Marwick, an archaeologist at the University of Washington who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email.

"There are older examples of more generic rituals, such as burial of the dead," Marwick said, "but this one is special because it is a specific ritual practice that has continued from time immemorial until recently."

While the archaeological work tying together 12,000-year-old ritual objects with 19th-century historical practices is a clear scientific triumph, it also points to a loss of Indigenous knowledge with the colonization and Westernization of Australia, according to Mullett.

Ethnographer Alfred Howitt recorded Gunaikurnai rituals in 1887, but "if he wasn't there, that knowledge may not well have been transferred on," Mullett said. "Because we're talking about times of mission stations, where the severing of cultural knowledge is occurring."

"The science can only tell you so much," David told Live Science in an email. "Incorporating traditional cultural knowledge provides an opportunity to tell a broader story about the Old Ancestors and the cultural landscape they lived in."

Kristina Killgrove is an archaeologist with specialties in ancient human skeletons and science communication. Her academic research has appeared in numerous scientific journals, while her news stories and essays have been published in venues such as Forbes, Mental Floss and Smithsonian. Kristina earned a doctorate in anthropology from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and also holds bachelor's and master's degrees in classical archaeology.