'Planet killer' asteroids are hiding in the sun's glare. Can we stop them in time?

In the glare of the sun, an unknown number of near-Earth asteroids move on unseen orbits. A new generation of space telescopes could be our best defense against potential disaster.

On the morning of Feb. 15, 2013, a meteor the size of a semitrailer shot out from the direction of the rising sun and exploded in a fireball over the city of Chelyabinsk, Russia. Briefly glowing brighter than the sun itself, the meteor exploded with 30 times more energy than the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima, exploding some 14 miles (22 kilometers) above the ground. The blast shattered windows on more than 7,000 buildings, temporarily blinded pedestrians, inflicted instantaneous ultraviolet burns and otherwise injured more than 1,600 people. Fortunately, no known deaths resulted.

The Chelyabinsk meteor is thought to be the biggest natural space object to enter Earth's atmosphere in more than 100 years. Yet no observatory on Earth saw it coming. Arriving from the direction of the sun, the rock remained hidden in our biggest blind spot, until it was too late.

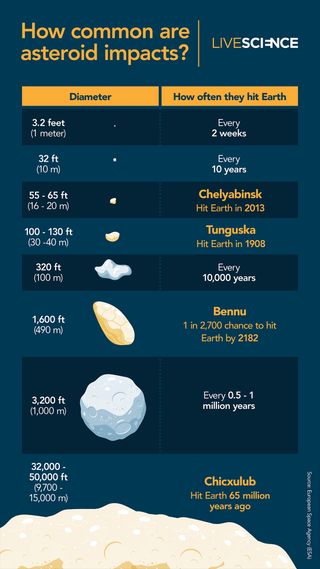

Events like these are, fortunately, uncommon. Rocks the size of the Chelyabinsk meteor — roughly 66 feet (20 meters) wide — breach Earth's atmosphere once every 50 to 100 years, according to an estimate from the European Space Agency (ESA). Larger asteroids strike even less frequently. To date, astronomers have mapped the orbits of more than 33,000 near-Earth asteroids and found that none pose a risk of hitting our planet for at least the next century.

But you can't calculate the risk of an asteroid you can't see — and there are untold thousands of them, including some large enough to destroy cities and potentially trigger mass-extinction events, moving on unknowable trajectories around our star, experts told Live Science. It's a harsh reality that has astronomers both concerned about the possible consequences and motivated to find as many of our solar system's hidden asteroids as possible. Once we know about them, deadly asteroids can either be monitored and deflected if needed, or if all else fails, populations can be warned to relocate to avoid mass casualties.

"The most problematic object is the one you don't know about," Amy Mainzer, a professor of planetary science at the University of Arizona and principal investigator for two NASA asteroid-hunting missions, told Live Science. "If we can know what's out there, then we can have a much better estimate of the true risk."

Related: NASA's most wanted: The 5 most dangerous asteroids in the solar system

Killers from the sun

At any moment, the sun hides countless asteroids from view. This includes a constantly rotating cast of Apollo asteroids — near-Earth objects that spend most of their time far beyond the orbit of Earth but occasionally cross our planet's path to swoop closer to the sun — as well as the mysterious class of asteroids called the Atens, which orbit almost entirely interior to Earth, ever on the planet's dayside.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Aten asteroids are the most dangerous, because they cross Earth's orbit just barely at their most distant point," Scott Sheppard, a staff scientist at the Carnegie Institution for Science, told Live Science. "You would never see one coming, to some degree, because they're never in the darkness of the night sky."

As with all asteroids, the majority of these hidden space rocks are likely small enough to burn up completely in Earth's atmosphere upon contact. But it's estimated that there are also many undiscovered asteroids measuring more than 460 feet (140 m) in diameter — large enough to survive the plunge through the atmosphere and cause catastrophic local damage upon impact, Mainzer said. Asteroids with this destructive potential are sometimes dubbed "city killers."

"We think we've found roughly 40% of those asteroids in the 140-meter neighborhood," Mainzer said. According to NASA estimates, that leaves about 14,000 left to be found.

There may also be far, far bigger objects awaiting us in the sun's glare. Though exceptionally rare, a handful of "planet killer" asteroids — which measure more than 3,280 feet (1 km) in diameter and are capable of kicking up enough dust to trigger a global extinction event — may lurk in the sun's glare, Sheppard said.

In 2022, Sheppard and his colleagues discovered one such planet killer obscured by the sun, which they described in a paper in The Astronomical Journal. The researchers were hunting for asteroids near Venus, borrowing time from several large telescopes to scan the horizon for five to 10 minutes each night at twilight, when they discovered 2022 AP7 — a mile-wide (1.5 km) behemoth with a quirky five-year orbit that makes the giant space rock almost permanently invisible to telescopes.

"When it's in the night sky, it's at its furthest point from the sun, and it's very faint," Sheppard said. "The only time it's somewhat bright is when it's interior to Earth, near the sun."

Currently, 2022 AP7 crosses Earth's orbit only when our planet and the asteroid are on opposite sides of the sun, making it harmless. However, that gap will slowly narrow over thousands of years, bringing the two objects closer and closer to a potentially catastrophic collision. And it's likely not the only one.

"Through our survey to this date, we find that there's definitely several more kilometer-size Aten asteroids out there to be found," Sheppard added.

Related: Could scientists stop a 'planet killer' asteroid from hitting Earth?

A blinding puzzle

Surveying asteroids near the sun poses a unique challenge for astronomers. Most space-based telescopes gaze toward the planet's nightside, to avoid both solar glare and radiation damage. Ground-based telescopes, meanwhile, face even greater restrictions.

"Not only is the glare of the sun a problem, but the timing is a big problem as well," Sheppard said. "The sun has to set to a certain position below the horizon before they even let you open the telescope, and the sky has to be just dark enough where you can take images and not saturate."

Once the sun reaches this fleeting position, ground-based telescopes have less than 30 minutes to survey the area near the edge of the sun before it dips below the horizon and disappears from view entirely, Sheppard added.

During this brief window, ground-based telescopes have the added challenge of peering straight through Earth's atmosphere, which appears thickest near the horizon and causes light from distant objects to flicker and diffuse. Gases in the atmosphere also absorb many wavelengths of infrared light — the thermal radiation that astronomers use to detect some of the faintest, coolest objects in the universe.

It's hardly an ideal scenario for spotting small, dark, fast-moving chunks of rubble.

"That's why you need to go to space," Luca Conversi, manager of ESA's Near-Earth Object (NEO) Coordination Centre, told Live Science.

Salvation in space

Orbiting hundreds of miles over Earth and far beyond, space telescopes are free from the distorting effects of the planet's atmosphere. This unlocks a powerful tool in their arsenals: infrared imaging, or the ability to detect heat coming off of space objects, rather than just the reflected sunlight that makes objects detectable by visible-light telescopes.

"Only a small portion of an asteroid's surface is illuminated by the sun, even in space," Conversi said. "So instead of looking at sunlight reflected from the surface, [infrared telescopes] look at the thermal emission of the asteroid itself, so we're able to find it."

This means that even asteroids that are visually dark, like the recently visited asteroid Bennu, shine "like glowing coals" when seen in infrared, Mainzer said.

Currently, there's only one infrared space telescope that's actively looking for near-Earth asteroids — the Near-Earth Object Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or NEOWISE. Launched in 2009 as simply WISE, the telescope was designed to detect objects far from Earth. But in 2013, after the Chelyabinsk incident, WISE was roused from a two-year hibernation as NEOWISE, with new software and a new mission to detect potentially troublesome near-Earth asteroids.

But NEOWISE was never able to look toward the sun — and its mission is expected to end for good by July 2024, Mainzer said. That will leave new asteroid detection solely in the hands of ground-based surveys until the next generation of space-based telescopes can launch later this decade.

"Go look up."

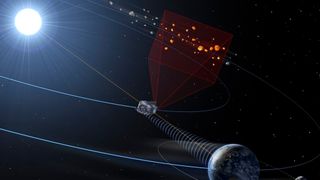

Two planned spacecraft should help to significantly demystify the dangers of the solar blind zone: NASA's NEO Surveyor, currently planned to launch in 2027, and ESA's NEOMIR, which is still in its early planning phase and will launch no sooner than 2030, Conversi said.

Both spacecraft will be equipped with infrared detectors and tall solar shades that will allow them to look for asteroids very near to the sun's glare, and both will orbit at the first Lagrange point (L1) between Earth and the sun, where the gravitational pull of the two objects is balanced. NEO Surveyor will complete a full scan of the sky every two weeks, splitting its focus evenly between the dawn and dusk sides of the sun, said Mainzer, the principal investigator for both NEOWISE and NEO Surveyor. The telescope is expected to primarily uncover near-Earth objects ranging from 50 to 100 m (164 to 328 feet) wide.

NEOMIR, meanwhile, would complement NEO Surveyor by scanning a ring-shaped area around the sun every six hours or so, Conversi said. Between the two spacecraft, even asteroids as small as the Chelyabinsk meteor should be spotted somewhere in their orbits long before impact, the researchers said.

"According to our predictions, NEOMIR would have seen the Chelyabinsk meteor about one week before impact," Conversi said. "More than enough time to alert the population and take some measures."

In the case of a small, Chelyabinsk-size meteor that explodes before reaching the ground, those measures could include alerting people in the impact zone to shelter and stay away from windows. Larger objects would hopefully be detected long before their date of impact, allowing people to evacuate the area if necessary. "Planet killers" require years of planning to safely deflect, but are also the easiest to spot far in advance.

But with both NEO Surveyor and NEOMIR years away from seeing the light of day, astronomers will continue to rely on the best ground-based methods available to parse the mysteries of the sun. Even with these spacecraft operational, a small percentage of near-sun asteroids will likely remain undetectable, Conversi said. Fortunately, the risks of a deadly impact remain low, and will hopefully only lower as astronomers gather more and better information.

"Go look up," Mainzer said. "Do a better survey, and you can greatly reduce the uncertainty."

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.

Most Popular